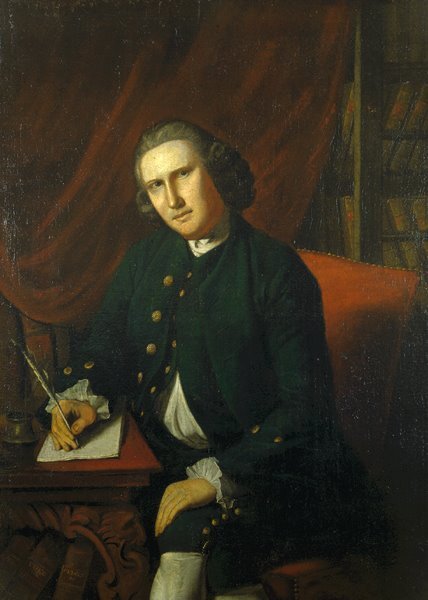

Samuel Chase

Maryland

On April 17, 1741, one life entered the world and another left it. On this Monday in spring, Samuel Chase was born to Thomas Chase, a rector of the Somerset Parish in Maryland, and his wife, Matilda Walker Chase. Sadly, Mrs. Chase died while giving birth to her son. Three years later, Mr. Chase and young Samuel moved to Baltimore where he was appointed rector of St. Paul’s parish. Rev. Chase educated his son at home teaching him Greek, Latin, literature, and history. The quality of the education matched that of a formal school. No doubt, as well, the Christian instruction he received from his father aided greatly in the strength of his Christian faith.

When Samuel reached 18 years of age, he moved to Annapolis to read law in the offices of Holland and Hall. During his time of apprenticeship at the law firm, he met William Paca. The two would form a lifelong friendship and Mr. Paca would also sign the Declaration of Independence and become a governor of Maryland.

During his apprenticeship, Samuel Chase’s financial state was less than ideal. When he married Ann Baldwin and for the next several years, they lived quite close to the poverty line. Once he was admitted to the bar and began his own practice, their quality of life improved. His client base consisted of mostly middle-class citizens and others who were refused representation by other lawyers. This affected his ability to grow his business monetarily. His clients were unable to pay or their payment for service was quite meager.

1764 was a pivotal year for Samuel Chase and the colonies. He decided to run for a seat in Maryland’s lower house of its General Assembly. He built an impressive coalition of those politically disaffected, clients, acquaintances, and others. His election to the lower house catapulted him to becoming a political force with power and influence. For the colonies, they found themselves about to be subjected to a tax they did not consent to, the Stamp Act. Furthermore, the tax on stamped paper was higher in American than it was in England. The colonists expressed great opposition to the tax, including Maryland. Lord Baltimore saw the act as a violation of the colony’s charter, which guaranteed the colony tax-free status.

Presumably, businesses could not function because they were required to use stamped paper, but they refused. Samuel Chase was a leading voice in this effort and continued serving clients by using unstamped paper. His leadership influenced the Frederick County Court to resume its service to the community. It also raised his stature and prominence in Maryland. He showed neither elite education nor societal status was a prerequisite for being influential and effecting change in politics. He was a member of the General Assembly until 1784.

In Annapolis, Samuel Chase and William Paca organized a Sons of Liberty group. The Sons of Liberty applied political and economic pressure to change policy rather than violence. The two friends strove to balance their opposition to the crown’s actions and their support for the home country. In the General Assembly, new blocs of anti-British sentiment arose. This development threatened to change the coalition that Mr. Chase and Mr. Paca had formed. They were less interested in joining in solidarity with the other colonies who were openly hostile to Parliament. Due to the pleas of other colonies, Maryland created a committee of correspondence in October of 1773. Mr. Chase was appointed to the group.

In 1774, the British Parliament passed the Boston Port Act, which closed the port in Boston until King George III had been compensated for the tea tossed into the harbor during the Boston Tea Party. This stirred up more opposition and when word about the act reached Maryland, Samuel Chase called for a boycott of British imports and colonial exports to the home country. Tensions with Parliament intensified in 1775. Mr. Chase believed only compelled obedience by threat of death would convince colonists to pay the taxes imposed upon them. In a letter to James Duane, a congressional delegate from New York, he wrote, “When I reflect on the enormous Influence of the Crown, the System of Corruption introduced as the Art of Government, … I have not the least Dawn of Hope in the Justice, Humanity, Wisdom or Virtue of the British Nation. I consider them as one of the most abandoned and wicked People under the Sun. … Our Dependence must be on God and ourselves.”

In the summer of 1776, as Congress was readying itself to debate Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence, Maryland remained uncertain of whether to embrace formal separation from England or not. Its delegates to the Continental Congress, Mr. Chase, Mr. Paca, and Charles Carroll, raced home to convince the Maryland Convention that independence was the right move. Convincing the body that reconciliation with England was no longer viable took two weeks. Public pressure forced the convention to authorize the delegates to approve Mr. Lee’s measure. Maryland joined the other colonies on July 2nd in voting for independence. Mr. Chase joined the others on August 2nd and signed the Declaration of Independence.

During the war, Mr. Chase served the United States in Congress by working on issues facing the Continental Army. Resources, such as food and munitions, were areas of constant need. He also inserted himself into the selection and promotion of senior army officers, including the appointment of George Washington to lead America’s military.

After the war, Samuel Chase held several judgeships until his last days. The most significant post he filled was a seat on the nation’s highest court, but his appointment by President Washington was met with some opposition. For most of his life, Mr. Chase had been an anti-Federalist. It was only after the war that he had shifted his views to comport more with the Federalists. The election of his friend, Mr. Washington, the adoption of the Bill of Rights, and the French Revolution’s impact on America changed his mind. There were some Federalists in the Senate who were less than accepting of his new found federalism. His nomination experienced some pushback, but, in the end, he was confirmed.

When Thomas Jefferson was elected to the presidency in March of 1801, he was intent on changing the nature of the Supreme Court by replacing the Federalists with anti-Federalists. Mr. Jefferson was an ardent believer in self-governance and believed federalism posed a threat to it. Samuel Chase was his target. Eight counts of offense were brought against him, but ultimately two-thirds of the Senate did not vote for his convection.

The trial had a lasting negative impact on him. Mr. Chase returned to the bench in debt, in poor health, and publicly disgraced. Whereas he once was a public force for the American Revolution, he retreated into private to assist Chief Justice John Marshall shape American jurisprudence. His health was quite poor at times and he missed the court’s sessions in 1807 and 1811. He died on June 19, 1811.

Samuel Chase lived to be 70 years of age.