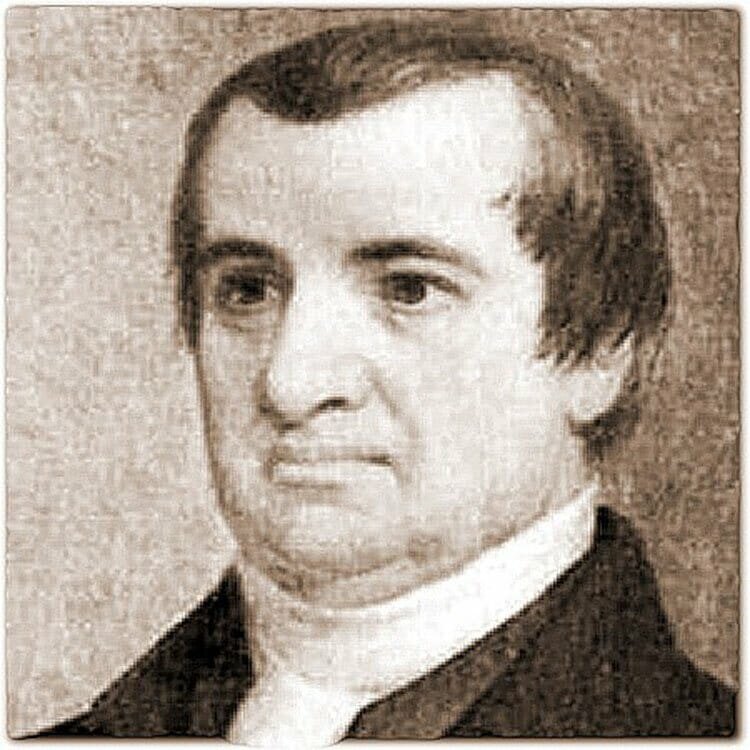

Abraham Clark

New Jersey

“Our Congress Resolved to Declare the United Colonies Free and Independent States. A Declaration for this purpose, I expect, will this day pass Congress, it is nearly gone through, after which it will be Proclaimed with all the State & Solemnity Circumstances will admit. … This seems now to be a trying season, but that indulgent Father who hath hitherto Preserved us will I trust appear for our help, and prevent our being Crushed; If otherwise, his Will be done.”

July 4th, 1776

Abraham Clark is considered to be the founding father closest to that of a typical colonist. He eschewed wigs and ruffled shirts. In a good way, he was obsessed with public service. He was referred to as “the poor man’s counselor” for he refused payment for his legal advice. This type of generosity for the good of the public dates back to his great grandfather, Richard Clark. Upon moving to Elizabethtown around 1675, people soon equated the Clark name with public service.

Abraham Clark was born into this family of rich service to others on February 15, 1726. He was educated in mathematics and surveying. He entered the field of surveying, but also studied law independently during this time. It is doubtful he was ever admitted to the bar. As a lawyer, he became popular for serving poor families who were embroiled in title disputes.

Before he served in the Provincial Congress of New Jersey, Abraham Clark was a clerk for the colony’s legislature. He was also the high sheriff of Essex County. In June of 1776, he and four other men were selected to represent New Jersey at the Second Continental Congress. Often, Mr. Clark would quarter with John Hart and Rev. John Witherspoon. Notably, one historian said regarding Mr. Clark and Rev. Witherspoon’s dedication to supporting and voting for the resolution of independence, “Both these worthy men had acted throughout on Christian principle and with a deep sense of their responsibility to Almighty God.”

On July 4th, 1776 Mr. Clark described the historical moment to a friend, “Our Congress Resolved to Declare the United Colonies Free and Independent States. A Declaration for this purpose, I expect, will this day pass Congress, it is nearly gone through, after which it will be Proclaimed with all the State & Solemnity Circumstances will admit. … This seems now to be a trying season, but that indulgent Father who hath hitherto Preserved us will I trust appear for our help, and prevent our being Crushed; If otherwise, his Will be done.”

Two areas Abraham Clark continued to focus on for the duration of the war are the eventual political structure of the country and the welfare of the Continental Army. Regarding the latter, he was involved in securing supplies for General Washington’s troops until the end of the conflict. And as it pertains to the former, Mr. Clark engaged in thoughtful critique of the shape of the future constitution. As early as August 1776, he was expressing the growing gridlock regarding states’ monetary obligation to the federal government and the number of representatives each state will be allotted in the Congress. He was quite involved in the debate surrounding these matters and others pertaining to the Articles of Confederation.

When it was time to update the country’s constitution at the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Mr. Clark was elected to be a delegate, but was unable to attend due to illness. In the years following, he served in the House of Representatives and also served as a trustee at First Presbyterian Church in Elizabethtown. He also, as a commissioner, helped to settle New Jersey’s accounts with the federal government. It is noted often in the recounting of his life that integrity, punctuality, and perseverance marked the character of his public service.

The fullness of his character is most readily revealed in this situation during the war. Abraham Clark’s two sons served in the Continental Army. During one particular encounter with the British, they were captured and imprisoned in debasing conditions aboard the prison-ship, Jersey. Until there was an instance of gross neglect on the part of the British guards, did he raise the issue to Congress. Thomas Clark had been cast into a dungeon and was not being given food by the guards. The food he did obtain was given to him through the door’s key hole by fellow prisoners.

Abraham Clark did not raise the issue with Congress earlier for he “did not believe men in public office should use their positions to confer favors on members of their personal families.” Congress threatened a British officer in retaliation for the poor treatment of Mr. Clark’s son. The British bent and he was released from the dungeon, but not from the ship. Both sons were held until an exchange of prisoners took place. During their imprisonment, Mr. Clark was offered a bribe by British leadership. They promised to release his sons if he became a traitor and pledged allegiance to the crown. He refused.

Mr. Clark finished his second term in the House of Representatives in 1794. A short time later, he was stricken with a sunstroke while in the place of his birth, Roselle. (This was also his home for all of his life.) The effects were grave. A few hours later, America’s public servant died on September 15, 1794.

Abraham Clark lived to be 68 years of age.